BEAST

Pushing the frontier of exoplanet surveys

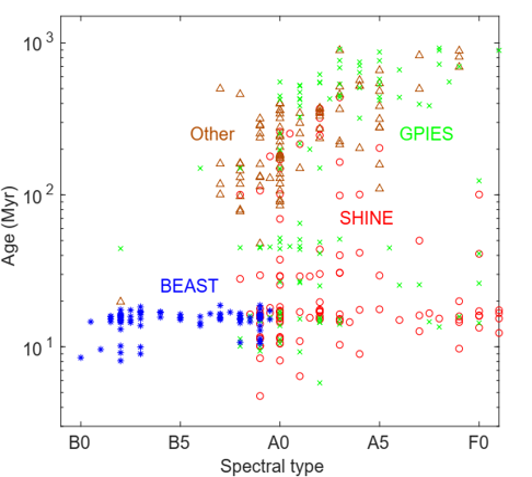

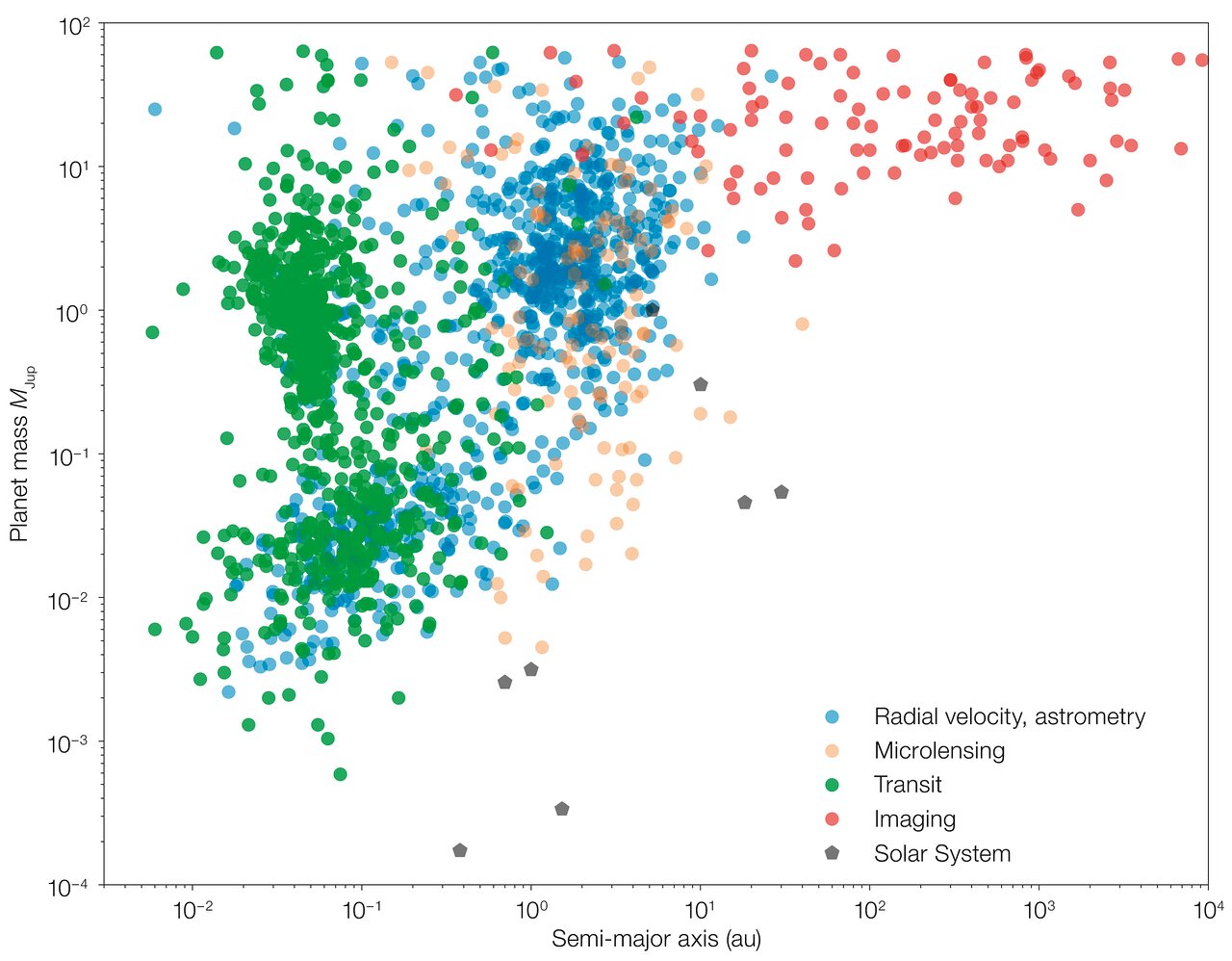

Most of the past and ongoing exoplanet surveys have focused on stars as massive as or less massive than the Sun, and about 90% of the ∼4500 known exoplanets lie closer to their stars than the Earth is to the Sun. What lurks in the outskirts of high-mass stars systems, waiting to be discovered? This is the scientific question that the B-star Exoplanet Abundance Study (BEAST) is trying to answer.